Exclusive Visit Inside Canon’s Lens Factory: A Surpising Look at Where Its Lenses Come To Life

Table of Contents

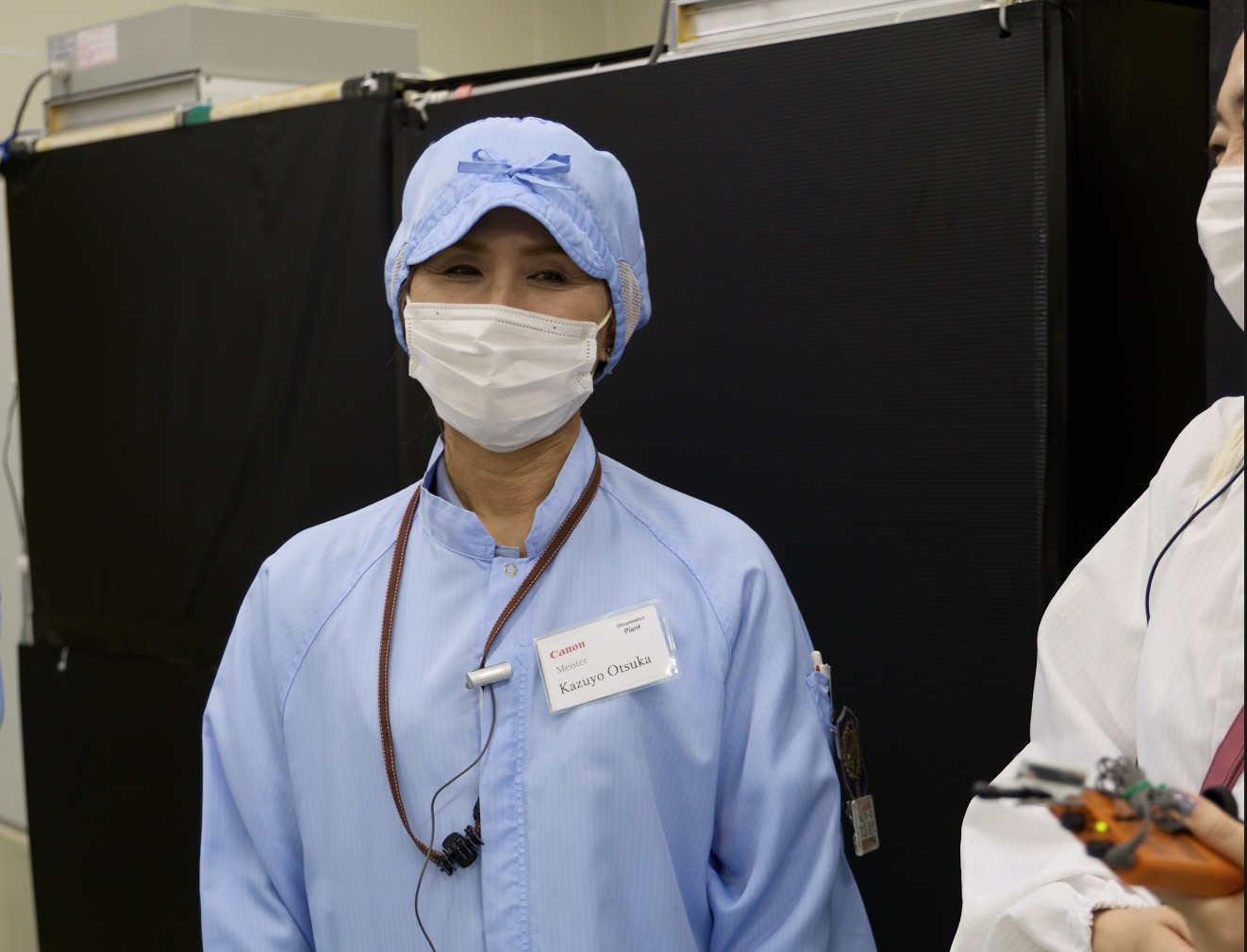

In a nondescript office building in Utsunomiya, Japan, a good portion of Canon’s lenses are planned, designed, manufactured, and, for some, lovingly hand assembled. If you’ve owned an EF or RF pro telephoto lens in the last 35 years, it was ushered into existence by Kazuyo Otsuka, one of the company’s “meister” artisans, whom I met on an exclusive tour of the factory.

Invited to the facility along with just a few outlets, Canon offered us a deep look into their manufacturing processes, a look that no journalists have had before. Even the Canon USA product and project managers travelling with us hadn’t seen the production lines.

If you’re imagining, as I did, rows of gleaming Terminator-style robots cranking out lenses without human interaction, you’d be wrong. Canon’s lens manufacturing is an incredibly hands-on process, a craftsman-centric approach to making the lenses that looks more like the shop of someone who lovingly restores vintage cars. Think Star Wars rather than Star Trek.

If you’re wondering like us why lenses like the Canon RF 100-300mm f/2.8 L IS USM are nearly impossible to find, we found out why.

The 100-300mm lens is backordered because the process of making them is laborious.. They’re assembled by hand, and the production team can only produce around nine of them a day and still maintain their quality standards.

Let that sink in for a moment. The $10,000 Canon 100-300mm lens has a production rate of under two hundred a month.

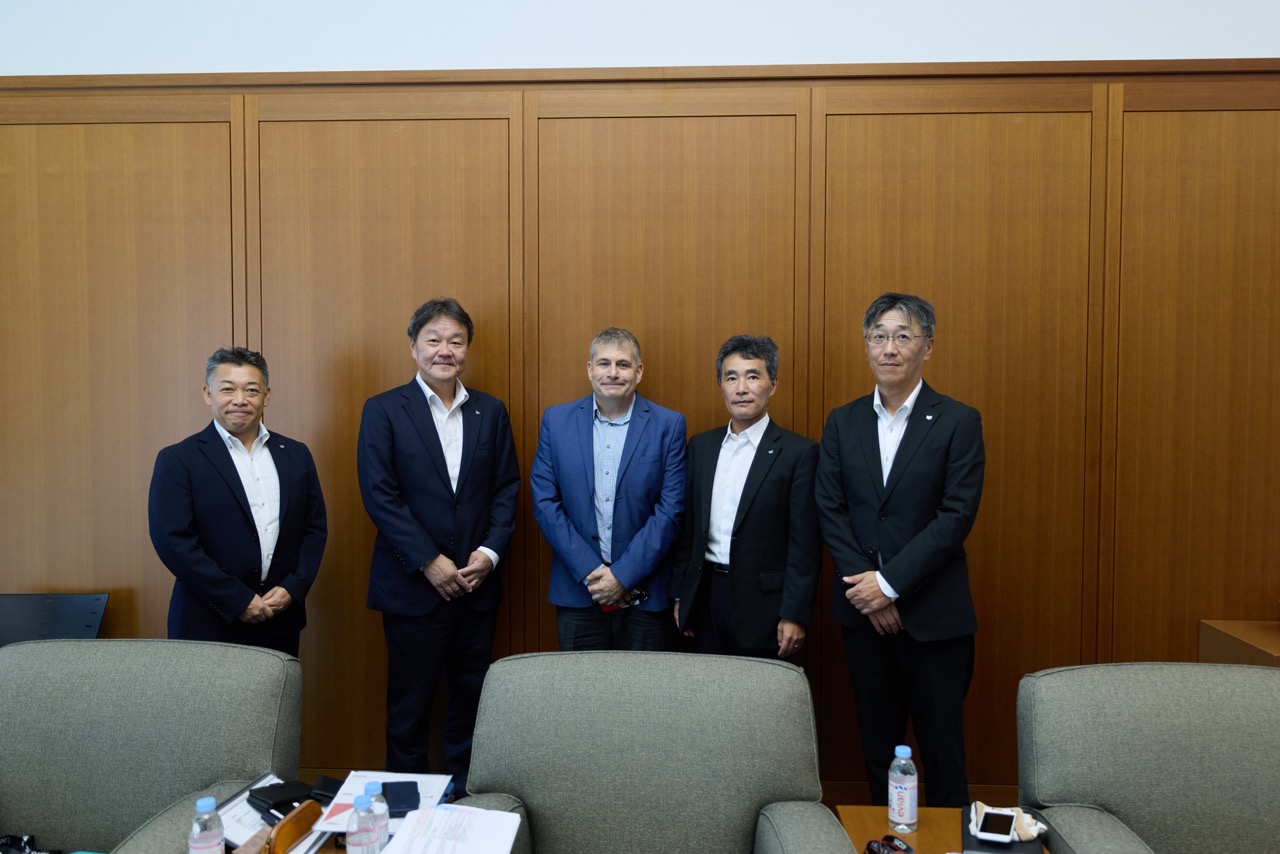

Secrets from the Executives

We expected to see many PowerPoint presentations, which are a big part of meetings in Japan. But I was not expecting the openness from the most senior imaging executives when answering questions. Some of the answers were more frank than anything I’ve heard Canon say before.

In a sit-down interview with the most senior staff in the imaging divisions, I was allowed to ask any question I wanted, not just a pre-approved question. This is practically unheard of in the camera world; usually, the executives pre-vet the media questions.

I started by asking if, being behind Sony in the mirrorless market, they’d seen any advantages in the delay. I wanted to know if there were things that they were able to bring to the R-series by taking time to catch up that benefited them when they entered the new mirrorless era. “Did that allow Canon to look farther down the road…to find an opportunity?”

“When we entered the full-frame mirrorless market,” said Mr. Manabu Kato, Chief Executive of IMG Business Unit 1, “it was in 2018. At that time, we were indeed behind Sony.”

That might be the first time I’ve heard a Canon executive admit that they were caught unprepared.. Generally, Canon has talked about the strength of their DSLR system and their plans only to bring mirrorless to market when the time was right.

Our lineup of cameras now stretches from the R1 to the R100,” he continued, “with more than 60 lenses. At this point, we don’t feel like we’re behind them.”

The most surprising answer came when I asked how they felt about stopping development on the EF lens mount, having been Canon’s standard for twenty years before the transition to mirrorless and the RF mount.

“By evolving the EF mount into the RF mount, we gained advantages like large aperture, short back focus, and high-speed communication. Those opened up new worlds, so we saw it as a chance.”

“You learned what the EF mount could not do,” I asked, “and mirrorless gave you a chance to put all that into practice?”

Here’s the reply that surprised me. “Ultimately, we realized there were things the EF mount could no longer achieve. As we sowed those seeds, the mirrorless era arrived, and the opportunity became real.”

That’s the first time I’ve ever heard Canon say they were developing the RF mount before mirrorless cameras. Likely, we would have seen DSLRs move to the RF mount even if mirrorless cameras had not become the norm.

When mirrorless took over from DSLR, the older SLR cameras were reaching the end of their practical development life. Autofocus was limited by the need to use a separate focusing module, but perhaps the EF mount was a bottleneck in their development, too.

By the Numbers

Through many PowerPoint presentations, Canon laid out its strategy for camera and lens development. As expected, they talked about how dedicated they are to innovation and detailed all the development and manufacturing processes they have pioneered.

They talked about one of Canon’s key strengths being the in-house development and manufacturing of all of the key components of the cameras. It’s not the first time I’ve heard a camera manufacturer talk about this advantage. Sony has often said that their ability to develop camera bodies, sensors, and lenses gave them the ability to sprint into the mirrorless market, and to create bodies that would take advantage of future lens technology and lenses that could unlock the potential of the cameras.

This in-house development, or lack of it, is something that really hurt Nikon’s mirrorless plans. It was buying the sensors from Sony and designing the processors in-house. Buying sensors from your competitors is an overall bad business strategy.

The Slow Pace of Incremental Improvements

Canon has been producing SLR cameras since 1937, and while some of the improvements in gear happen rapidly, most changes are incremental. The switch to digital occurred relatively quickly in the scale of photographic history, but most of the time, camera and lens updates have minor changes, though there might be technologies in updates that were a decade in the making.

Many of the presentations talked about the improvements new technologies are able to bring to Canon’s products, but it was surprising to see how much work goes into these often minor improvements.

Canon spends an enormous amount of R&D on technologies that improve the shooting experience, though some of these improvements may not even be noticeable to the average user. They result in better images, if only marginally better, though the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

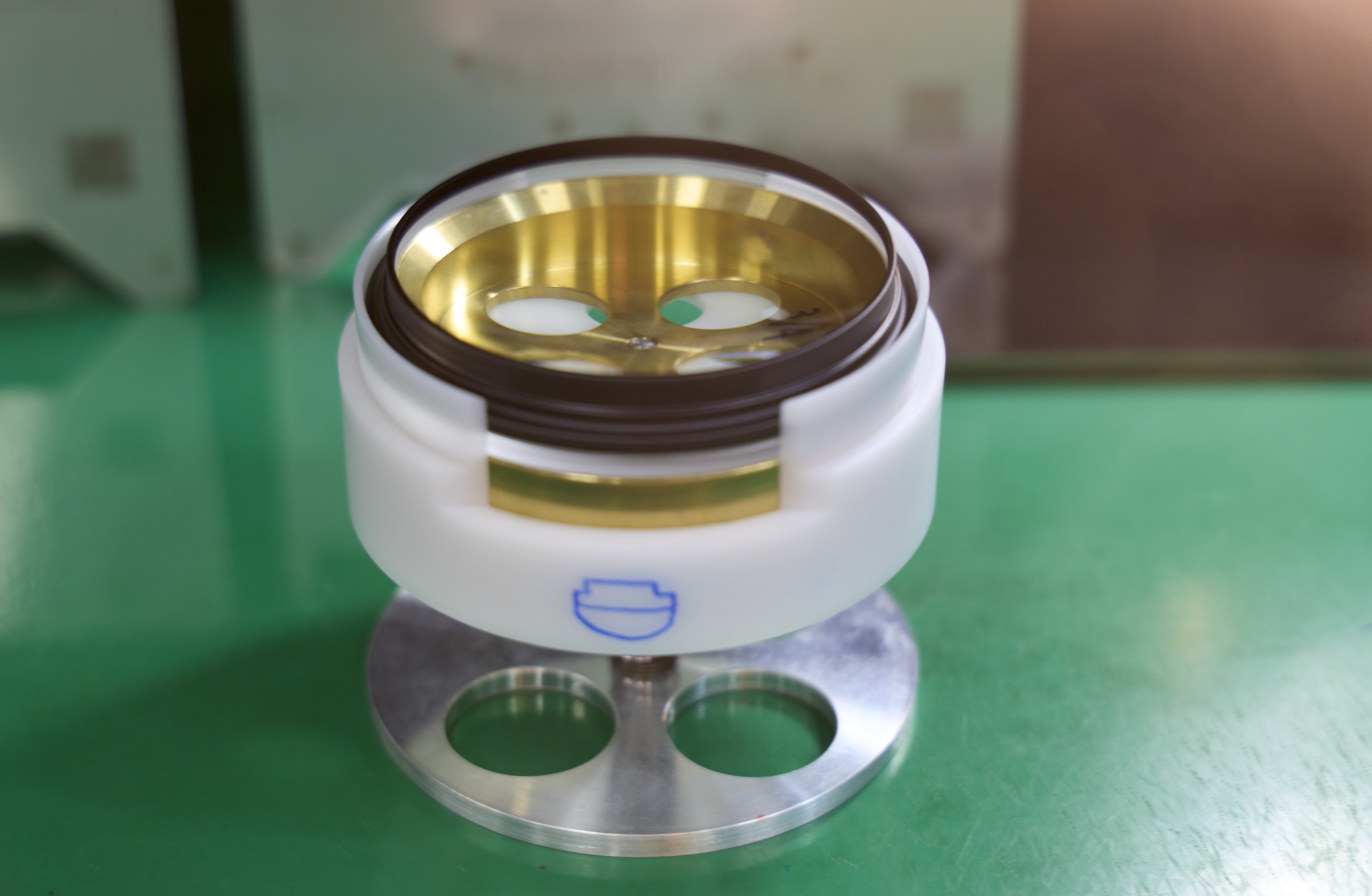

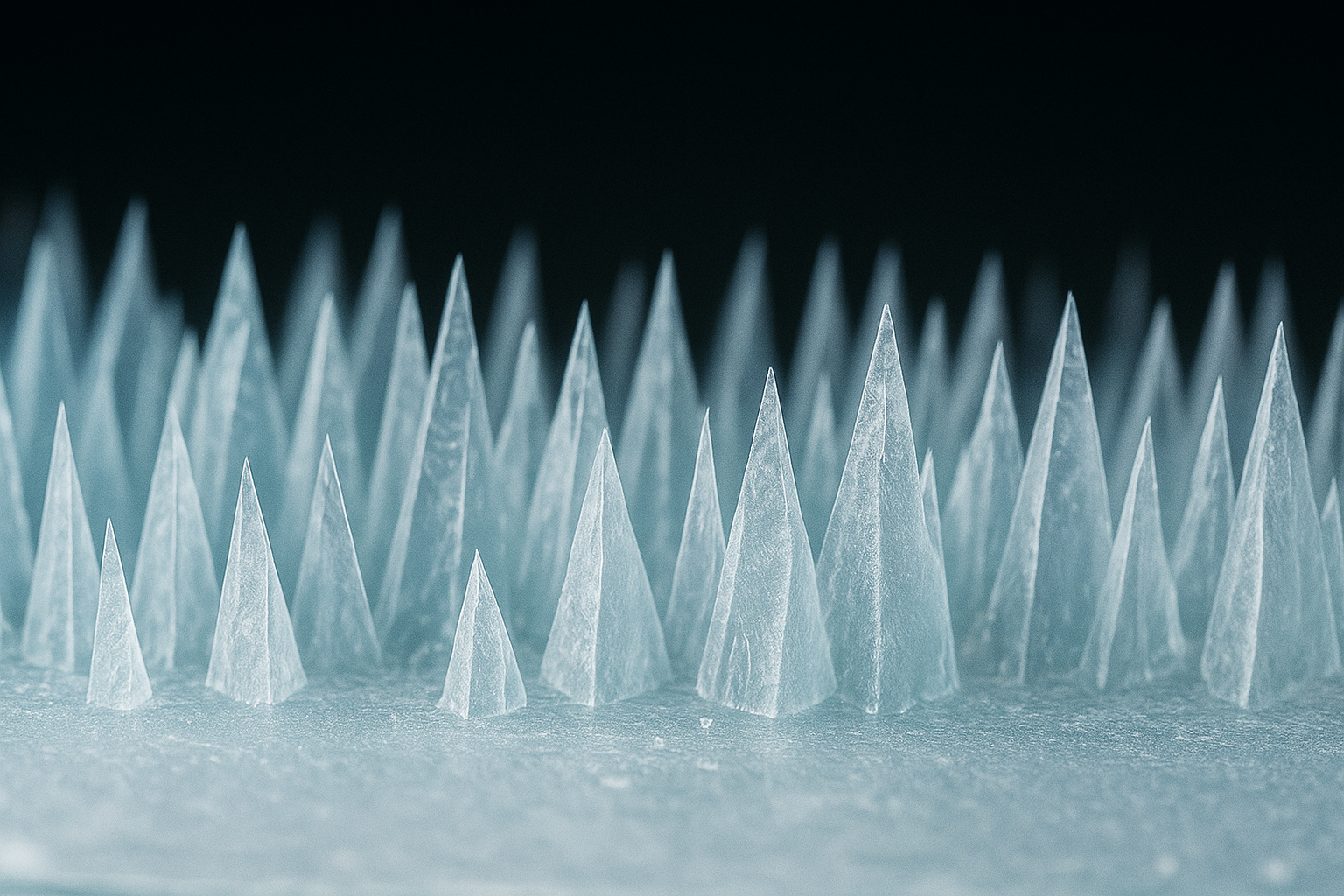

In one of the meetings, lens engineers described a technology they invented called Subwavelength Structure Coating, also called SWC, and it’s used in conjunction with another Canon technology, Air Sphere Coating.

The goal with SWC and the Air Sphere Coating is to reduce flaring and ghosting in lenses.

Canon coats SWC lenses with a series of nano-scale spikes that sit between the light and the lens surface. Canon says these nano spikes ease the path of the light from the air to the lens. You can think of this like slowly getting into a cold pool versus jumping in headfirst.

But can you see the difference in practice? Yes? Maybe? Sometimes? Anything that makes an image better is good, but in most images, they showed us the improvements are subtle.

So Why Bother?

Everything in photographic gear is either an incremental change and improvement or the result of many incremental improvements. Nano spikes on a lens might not radically change images, but Canon didn’t spend a decade on the technology to revolutionize photography. They made SWC to improve overall image quality over lenses without it. At some point, Canon will combine Subwavelength Structure and Air Coating with some new technology, and image quality will improve again.

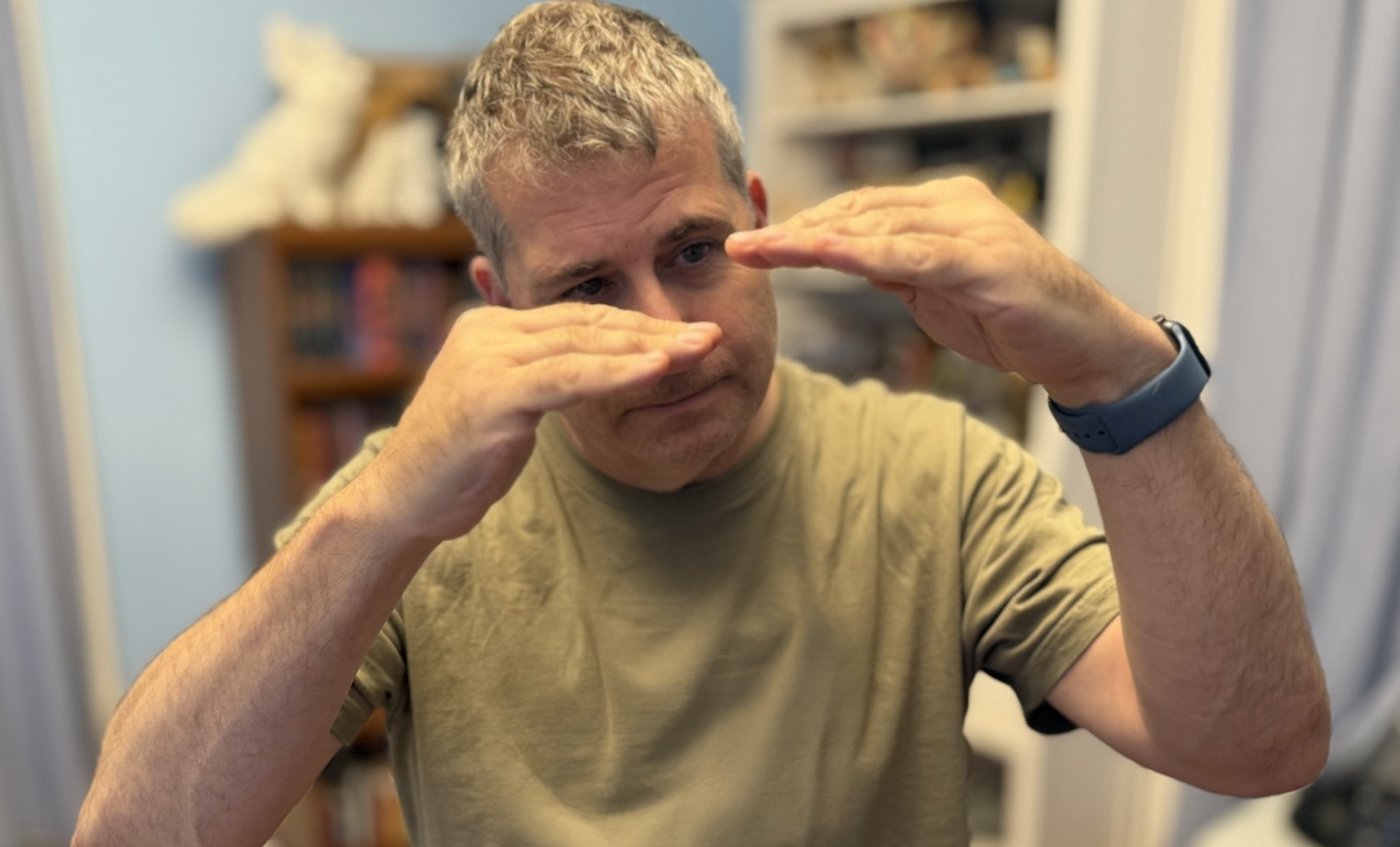

Chris Niccolls of PetaPixel and I were chatting between meetings about the improvements we were being shown. ‘I think I get it,’ I said. ‘Lenses are good-lenses with SWC are a little bit better,’ and I made the gesture where you hold one hand flat and then hold another just above it to show a slight improvement.

I would do this multiple times on the factory tour. While I found this running joke amusing, it’s the point of what most R&D does.

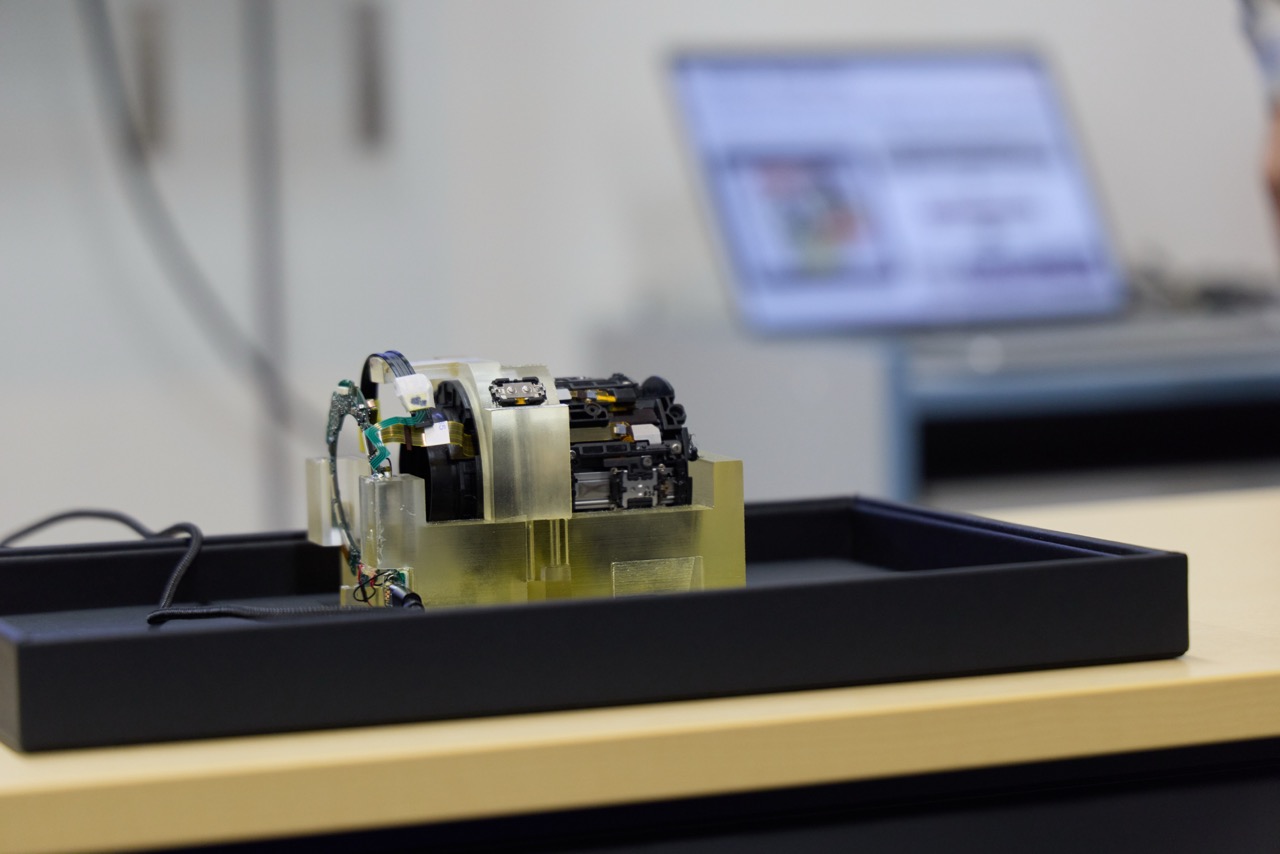

Canon also showed us IBIS versus IBIS combined with the Periphrial Coordinated Control system in their Optical Image Stabilized (OIS) lenses. Perirperal control works to reduce the distortion in the very corners of an image that IBIS itself can’t correct for. It’s a subtle difference.

We were shown issues, and while the corners were better, I would not describe them as radically different. The effect is similar to using lens correction profiles to adjust for lens distortion.

“IBIS is good,” I said, making the gesture, “but IBIS with Periphreal Coordinated Control is better.”

I repeated the gesture after seeing how Canon uses deep learning to make auto white balance more accurate, especially for the blue cast that a clear sky often causes. “Auto white balance is good, deep learning auto white balance is better.”

And then I made it again when they showed the benefits of AI-based sport detection over traditional AI-based subject reaction. “Autofocus is good, sport-based autofocus is better.”

See the pattern here? While it was a good running joke, it turned out to be more accurate than funny.

Each time Canon showed us some advance in technology, it seemed minor in its own context, but Canon’s been at this for more than eighty years, and these little changes add up.

Take a lens with Periphreal Coordinated Control, put a SWC coating on it, and mount it to a camera with action-based AF and better white balance control, and now these little steps add up to a much more powerful system.

Inside Canon’s Off-Limits Lens Factory

The next day, we got a deep dive look, complete with clean suits, through Canon’s lens factory. Canon has never offered a tour of their lens production before, and having been on lens and camera factory tours with other manufacturers, I was surprised by how much access they gave us.

Japanese culture is known for having people who dedicate their lives to a single pursuit. A Tōkō master creates gleaming and polished swords. A Geijutsuka makes the most intricate pottery. And, it turns out, there are artisans of lens polishing and lens assembly.

Canon introduced us to their “meisters”, their collection of employees who have been working for decades to hone the craft of lens construction and assembly. Other companies might have similar craftspeople, but they’ve never been made available to the press.

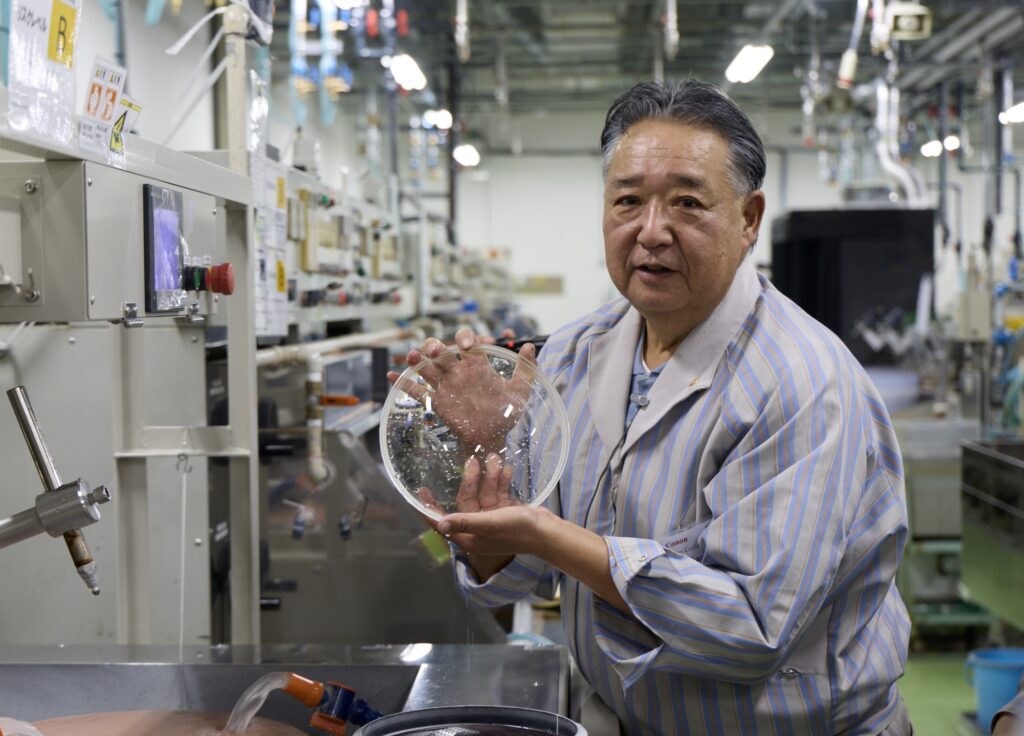

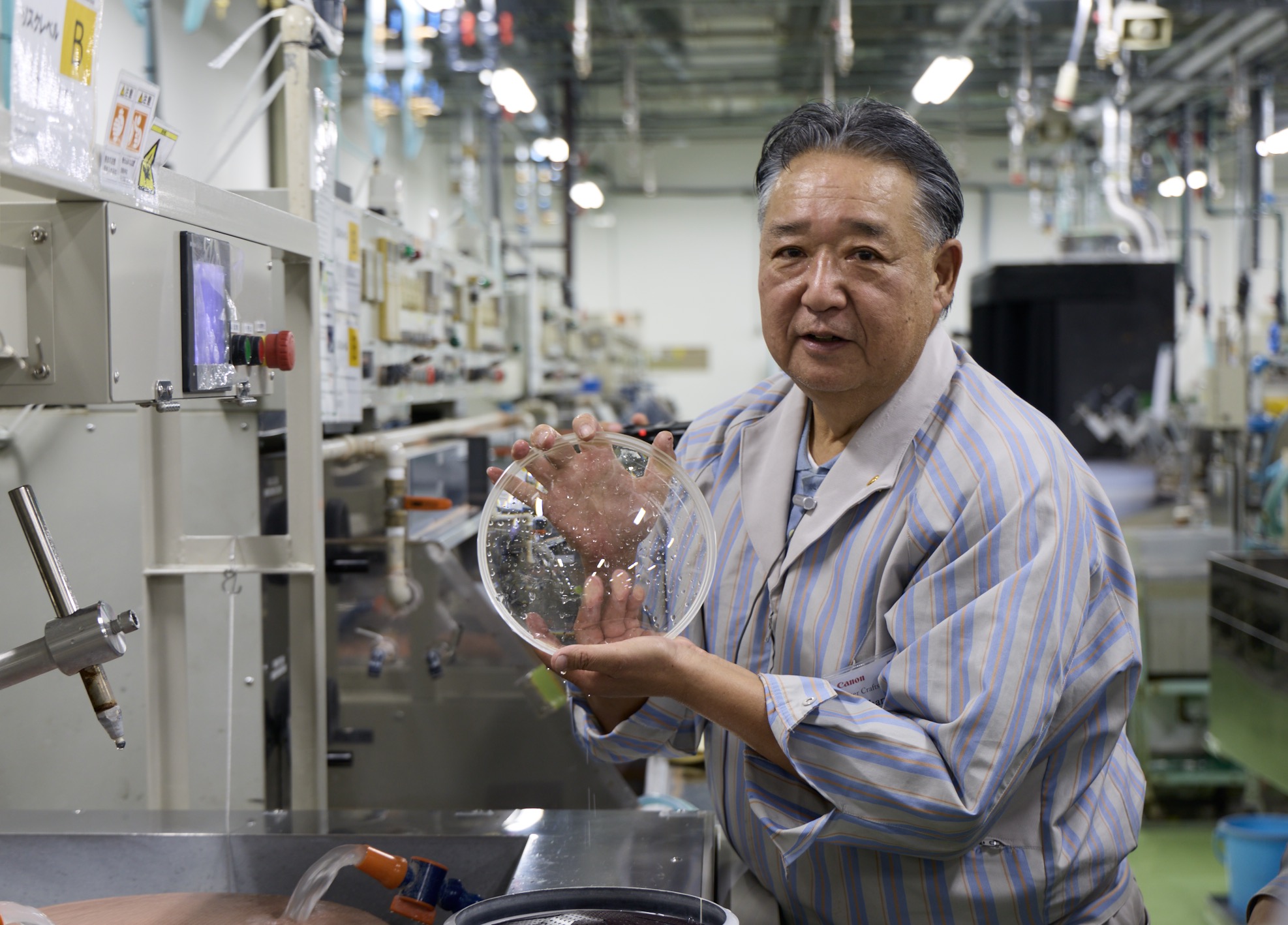

Mitsuharu Umei is Canon’s lens polishing meister, and its lens assembly Meister is Kazuyo Otsuka. Both have worked in Canon’s lens production facilities for decades, and both are artisans.

We followed the path of a camera lens from glass to shipping container, starting with the polishing of the glass.

The Art of Making the Lens

In its marketing, Canon talks about the idea of monozukuri. “It can be literally translated as ‘making things’ or ‘crafting things’ (‘mono’ meaning thing, and ‘zukuri’ meaning the act of making),” Canon Europe’s website explains. “But it is so much more than that. Conceptually and culturally, it reflects-and respects- the soul and art of the maker.

Mitusharu Umei is Canon’s meister lens crafter, and Umei-san hand-polishes lenses with unbelievable precision. He is the embodiment of monozukuri.

For some lenses, the tolerances are fractions of a millimeter. Umei-san told us that for a large-diameter TV broadcast lens, if the lens were the size of Dodger’s Stadium, the tolerance would be less than the thickness of a piece of paper. Umei-san can polish lenses to this tolerance by hand.

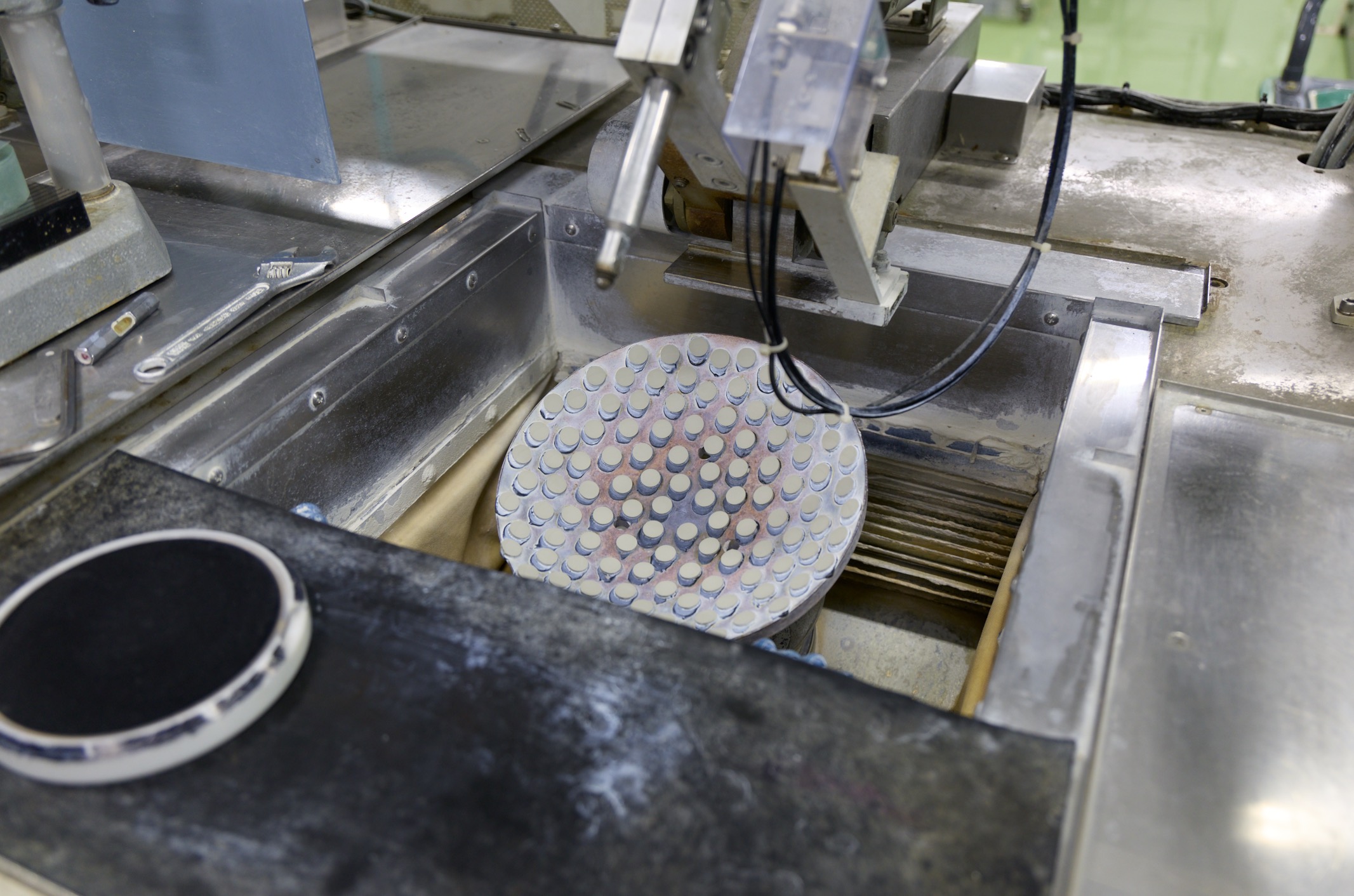

We walked through rows of equipment used to polish glass, boxes with nozzles that spray abrasive or water to take a lens from raw and opaque glass to a final piece of optics. These lenses work their way through a series of steps, including hand-polishing the glass on diamond-coated spheres.

Umei-san has been honing his craft at Canon for thirty-seven years. Put another way, I’m 55 and Umei-san has been learning the art of glass polishing since I was in college. He told us it might take a decade or more for an apprentice to develop the skills needed to make the lenses that require the most accuracy.

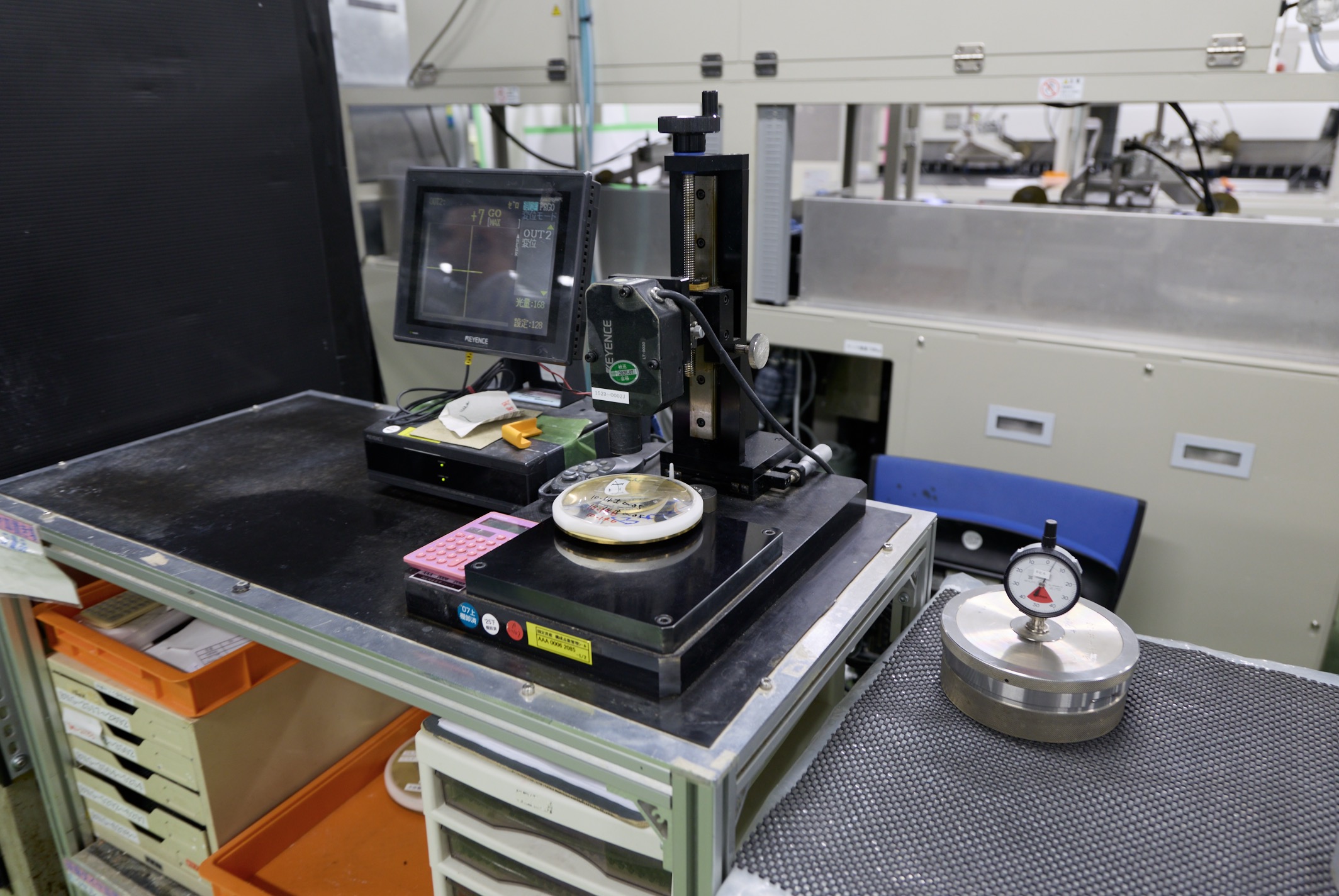

He had us test our skills on a large polishing machine, and I made the mistake of going first. A rotating base holds the glass, while a disc the size of a small pizza has to be pressed onto that rotating glass. The task takes two hands and is like patting your head while rubbing your stomach. I am, it turns out, never going to be a master craftsman at Canon as I nearly spun the disc off the rotating base.

Not all Canon lenses are made by hand, though. Aspherical lenses are shaped like a bell and can’t be made by hand. Kit lenses and any lens element that requires a sophisticated molding or shaping process are done by robots.

Send in the Robots – Sophisticated Lens Shapes

One of the few machines we were not allowed to photograph makes these aspherical lenses in a totally automated process. A slab of glass is loaded onto a platform, which is then heated to the melting point, and then a machine presses it slowly as the glass cools. Through the window in the machine, we could see molten glass being forced into shape.

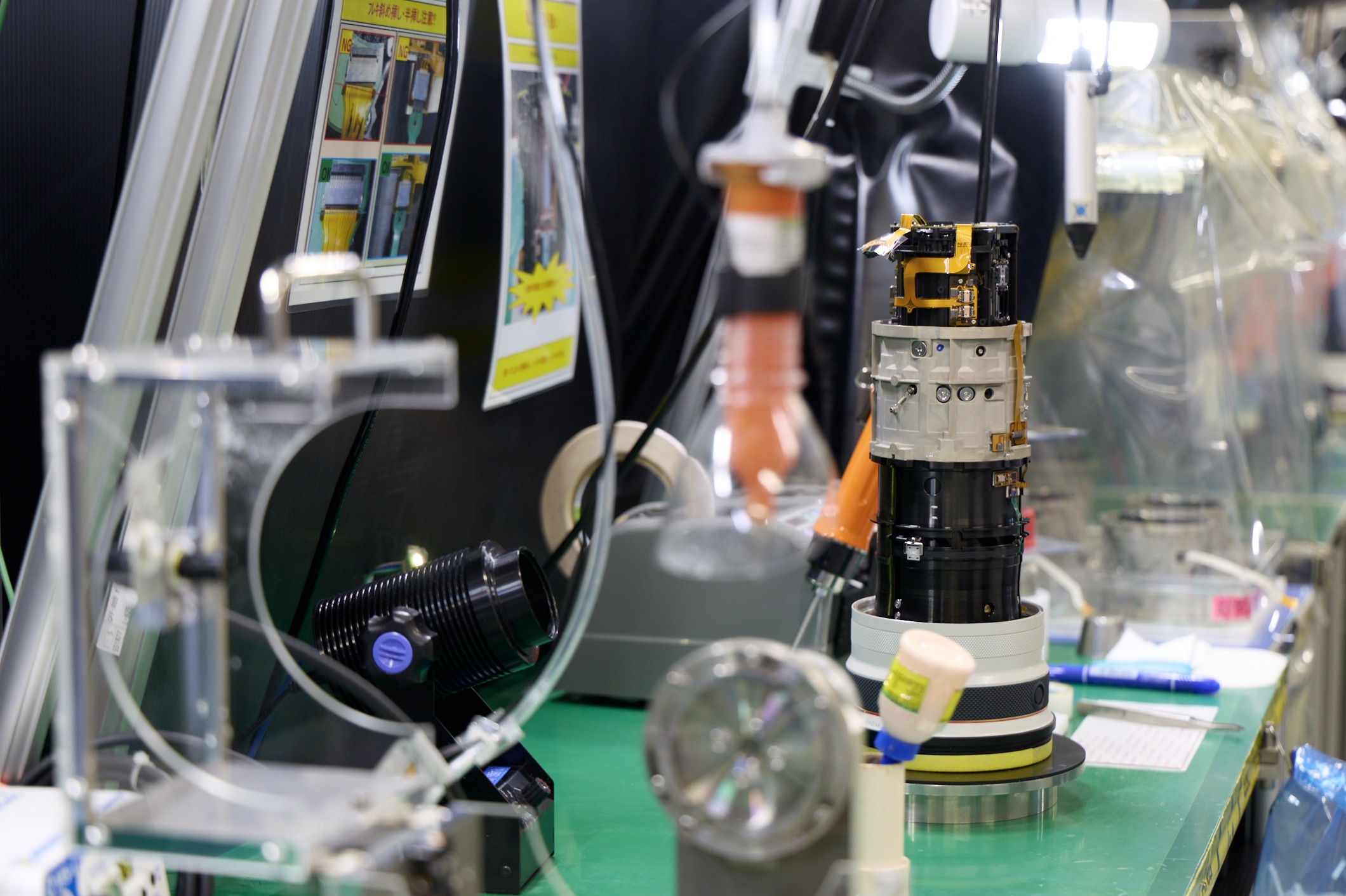

These slugs of glass go through polishing processes and then move to assembly. Another machine, which we also could not photograph, looked the most like the type of machine that might assemble a human-killing robot in a sci-fi movie. Robot arms turn, lift, and lower these lenses into the metal housings, pressing them into place and finishing them in a process that moves them automatically from robot to robot.

We couldn’t photograph these because they’re made in-house by Canon and have proprietary designs. Like a lot of the equipment at Canon, they look both futuristic and like something made by a mad scientist. Arms swing, automated quality assurance systems flash the results of the optical tests they make, but the boxes clearly look like they were made by hand instead of purchased off-the-shelf from somewhere.

Master Assembly – Every Lens Touched by the Same Person

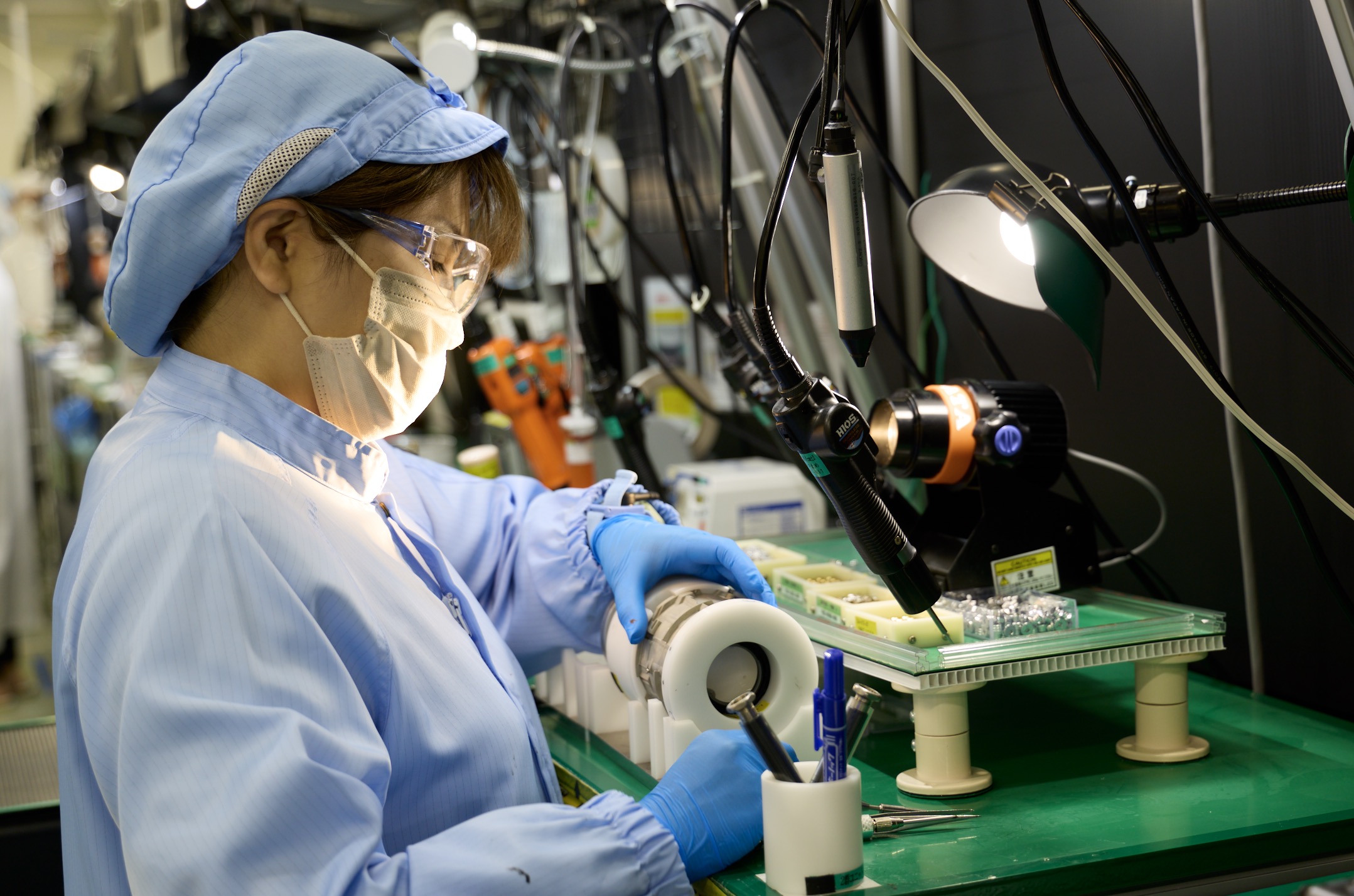

Canon’s lens assembly Meister is Kazuyo Otsuka. She works inside the clean rooms of the lens assembly facility, guiding the production of every super-telephoto lens Canon makes.

Otsuka-san has been a craftsman on this line for nearly forty years, and she said she considers each lens she has helped make one of her babies. I’ve been reviewing Canon lenses for more than twenty years, so I’ve unknowingly used dozens of lenses she made by hand.

I find it incredible to think that one person has had a hand in producing so many lenses, which ties all Canon shooters together. That wedding photographer with a 200mm lens? Otsuka-san. The birder with a 600mm? Otsuka-san.

Much of the camera and lens assembly is done by hand, mostly by women. When I toured Sony’s camera body facility years ago, and Nikon’s years before that, the staff explained that women tend to be more dexterous than men, and tend to have smaller hands that are more suitable for tasks like tightening millimeter-wide screws.

These jobs are not the monotonous assembly lines you might think of; the lines are small, making each member of the team more of a craftsperson than a widget. The meticulous attention to detail is what makes the production capabilities so small. You can have a handcrafted production team, or you can have an automated assembly line.

The Terminator Factory

Until this point, we had seen mostly processes carried out by hand. In the glass polishing area, tools were sophisticated versions of traditional tools. Diamond polishers sit next to manually operated washing and lubrication bays.

Not every lens can, or should be made by hand. Entry-level and enthusiast lenses are produced by robots, with the assistance of humans, instead of humans with the aid of robots.

One of the manufacturing lines we watched takes the aspherical blanks created in the automated lens creation process we saw earlier and fits them into their lens bodies. This robotic system is used for kit lenses and lenses with custom aspherics.

This area looks like the factories in the Terminator movies, but only slightly more so. The robotic assembly lines are created in-house by Canon. They look more like a mad scientist created them in a lab. They’re not gleaming white like a car production plant; they’re physical, mechanical tools that have been assembled, also by hand, for specific tasks. You can tell they were made in a machine room somewhere in the factory, not at the type of plants that make those killer robot dogs.

Quality Assurance

The most amusing part of the tour came in the quality assurance section. Here, prototype lenses and cameras are shaken, dropped, flung into a simulated wall, and subjected to extreme heat and humidity as well as extreme cold.

All of the QA tools are automated and repeatable. If you want to see how a camera survives a fall from a meter above the ground, you have to be able to repeat the text exactly. Seeing machines designed to drop a camera on its attached lens precisely makes me feel a bit better about the times I’ve dropped cameras. Clearly, I’m not the only one.

Canon also tests its shipping containers using these precise automated tools. If that $10,000 hand-assembled lens breaks on the way to B&H, all the effort is lost, as is the revenue. Seeing a box dropped onto a corner felt particularly comical.

Canon invited us into the hot and the cold chambers, and I can tell you nothing feels quite as bad as being in a room in the high 90s with 100% humidity while wearing a business suit, except then entering a cold room where the sweat instantly freezes.

The Takeaways from the Canon Factory Tour

I’ve been fortunate enough to have taken several factory tours over the years. In each one, the executives have been immensely proud of their processes and their approaches to producing the highest quality photography and video tools.

Most camera users I’ve talked to have no idea how much hands-on design and production go into their gear.

Every company has its own gleaming robotic production lines. Sony’s image sensor production lines are nearly completely automated and housed in a sparkling white clean room where only the team that maintains the equipment can be seen walking around. I’m sure Canon’s sensor facilities are equally gleaming.

Yet all of the companies have production lines like the ones for the 100-300mm lens, where people work precisely and efficiently to bring the product to life.

I have no idea if the other companies have the artisan “meisters” like Canon, partially because no company has given us such unprecedented access.

What’s clear is that Canon takes great pride in what they do. Every executive, every product manager, every factory worker expressed the happiness they get in moving technology forward.

Sometimes there are leaps in technology, and sometimes there are nearly imperceptible advances. If Canon had not shown us the nanotechnology they developed for their lenses, I might never have known about it, as the benefits are so subtle.

In Shinto, both a religion and a practice that nearly fifty percent of the Japanese practice, there is the concept of “tamashii,” the spirit that physical objects possess. The translation isn’t perfect, but it’s akin to a product having a soul.

To Canon, its products have tamashi, and everyone we met proudly talks about their commitment to bringing products to life.

It might not be readily apparent when you’re shooting portraits or capturing wildlife, but Canon believes they are bringing gear to life. Canon talks about their commitment to your gear being part of your photography or videography experience.

Since photographers consider their cameras to be part of their creative process, this makes sense. Canon makes its cameras and lenses with a purpose and a dedication to the art of image creation, just like you use that gear to bring your vision to life.

When showing off prototypes of the R1 and the C50, the team also showed a mint condition T90, the camera that formed the design directions for decades of Canon’s camera development. They handled it with care and precision, wearing white gloves to keep from marring the surface. But they also handled it with cotton gloves out of respect for the camera and how it launched Canon’s position in camera development.

The takeaway from the Canon tour is that the small improvements that each new technology offers are part of a larger goal of constantly improving. Some of these improvements come to life relatively quickly, and some of them take decades to bring to life.

The handcrafted nature of Canon lenses and bodies is something that connects all Canon shooters. The improvement designed at the Utsunomiya plant, and Canon’s many other design and manufacturing facilities, are tied together, making clear its goal of bringing its sense of creativity to all of its users.